Attention is All A Manager Needs

As I learn more about the current renaissance of Artificial Intelligence for something I am building (more on that at the end), I find myself reading and re-reading papers that talk about how to consume and make sense of information at scale.

All this talk about managing information at scale makes me think of challenges faced by engineering managers and directors as they have to deal with both information overload and scarcity simultaneously. This is a recurring major topic when coaching new managers or folks who made the transition from line manager to senior management. In this article, I am going to discuss the challenges and offer a few practical tools that have worked for me in my own journey.

The challenges with attention

Managing is a balancing act of where to direct one’s attention—knowing when to zoom in for details and when to zoom out for the bigger picture.

In modern organizations, this is made worse by the proliferation of multiple inboxes. Each tool used by teams on a daily basis (Jira, Slack, Workday, Expensify, etc.) comes with its own notifications and alerts system. As a manager, you find yourself having to check them all continuously, deciphering which issues demand immediate attention and which can wait.

Information overload is a huge pain point, consuming valuable time and draining your energy. On the other hand, the opposite challenge arises as well—relevant information often fails to reach you at the right time. Team members may not proactively share essential updates, and you may find yourself in the dark about the status of a critical task or project unless you explicitly request a status report.

The general challenges manifest themselves differently at different levels of management. Let’s take a look at some peculiarities of each one.

Engineering managers

When I am coaching an engineer or other individual contributor through the transition to management, usually the first challenge is shifting their attention from individual tasks to the team and project as a whole.

This change requires learning how to delegate and trust the team, but the most challenging step is understanding_ what_ needs your attention and where to look for it. Widening our lens can be overwhelming, and the new manager is usually terrified they won’t be able to provide a competent answer when their director or some important stakeholder asks about something.

How people deal with this depends a lot on their personality. More extroverted people tend to rely on talking to their team members to gather this information. While seemingly benign, this style can quickly devolve into a stream of interruptions for status reports and a team that is overloaded with meetings. In remote work, this is made worse by the inability to have quick, spontaneous conversations.

On the other hand, more introverted managers usually dread asking for status updates. They spend hours every day reading through Slack messages, Google Docs comments, and GitHub PRs rather than bothering someone for an update. It has the benefit of not breaking the team’s_ _flow, but the manager ends up with whatever imperfect information they are able to piece together from reverse engineering these artifacts. It also results in a misalignment between team members as, without synchronization checkpoints, it is natural that people drift apart and start behaving like many micro-teams instead of one single entity.

And even when they _have _a good picture of what’s happening, another attention-related challenge for the first-time manager is avoiding reactivity.

As a manager, you are exposed to an endless stream of activity that might impact your projects and people. A new manager will often fall into the trap of handling these issues as they arrive, dealing with each one individually. Resolving problems may feel productive, but if you don’t apply some strategy, you’ll quickly become a troubleshooter rather than a leader. You will spend so much time dealing with these issues that virtually no time will be left to do your actual job, which is to put in place whatever is needed to prevent these issues to begin with! Even when you have time, you will often be brain dead from hours of context-switching constantly.

Directors and above

After a lot of trial and error (and hopefully a good coach), most new managers find their way around managing information within their own team. They build a system that works well enough for their teams and start feeling less overwhelmed.

Unfortunately, this is usually the point in time they are given more scope to manage. Maybe they are assigned a second or third team or get promoted to senior manager or director. And that’s when they find out that knowing what’s happening in their team was the easy part. As their scope increases, the area their attention radar needs to cover also grows.

The role of a senior manager varies wildly with the kind and size of the company—much more than the engineering managers. What is always present, though, is an expectation that someone in this role will impact and support more than just their immediate teams and stakeholders. A lot of what a senior manager does is within the context of what Patrick Lencioni calls “first team”: the idea that the leaders in your group, i.e., you, your peers, and your leader, are a team in its own right, a team that will prioritize what’s in the interest of the overall organization and not just your individual groups.

The expectation exists regardless of the company’s maturity in implementing this idea of first team in practice. To fulfill it, senior managers need to be up to speed not just with their teams and projects, but also with what’s happening in peer teams and the whole organization.

Ultimately this means that not only do you need to be looking downward at your teams, you also need to look sideways across the organization.

With this widened aperture, trying to figure out what is happening by reading Slacks, PRs, Google Docs, and Jira becomes humanly impossible. Worse, now that you have a higher rank, people treat your asks for updates as a serious request from a superior. What could’ve been a one-line Slack response turns into a 30-minute walkthrough of an overly rehearsed 40-slide deck. You start being selective of what kind of updates to ask for and whom you ask to avoid people dropping everything they’re doing because “the boss wants a status report pronto.”

What has worked for me

As with so many crafts, learning how to deal with the challenges of growing in scope is often done by experience. While each manager’s path is unique, some practical advice holds true across most cases.

Build recurring information checkpoints

You may loathe the eight-hours-per-iteration-spent-in-planning thing suggested by early versions of Scrum, and I won’t blame you for that. But regular planning sessions, for both short and medium terms, are a good thing. Regularly scheduled planning sessions allow your team to take a break from the daily fog of war and think about the next few weeks or months.

Similarly, a regular daily “stand-up” creates a forum in which everyone is encouraged to broadcast what they are working on and self-organize around blockers.

It doesn’t matter how often they happen or how long they take, but regularly planned rituals like these do wonders for actionable information sharing. Firstly, the team can plan around these ceremonies instead of being interrupted by a manager’s ad-hoc requests for status updates. Even more importantly, they set the expectation that people should share information regularly and give folks “permission” to ask others for updates—something that might sound silly but is very important for less extroverted folks who may need the encouragement of being in a safe space.

Create a UX for information sharing—even if you need to fake it

The only thing worse than not having the information and context you need available in Jira or a document or anywhere else you can read without bothering someone is to have that information be outdated. And both issues are prevalent in organizations of all sizes.

You can try and force your team to be more diligent about keeping information up to date by being explicit that it is actually a core expectation of their role that impacts their performance. Or you can encourage good behavior by reminding them every time you ask for an update that the best way to keep you from interrupting is to make sure the information you need is available in the system.

But, carrot or stick, these will do only so much in improving the quality of information available to you and other stakeholders. The biggest issue preventing people from keeping information fresh isn’t forgetfulness or lack of care - it’s the user experience. I don’t mean the UX of tools like Jira or similar. These usually suck, but people learn to live with them. I am talking about the experience of the process end-to-end.

Typically, a team uses not one but multiple management systems, and they need to be kept in sync. People often spend too much time manually copying, pasting, and linking items between Jira and Trello, Github PRs, and various spreadsheets.

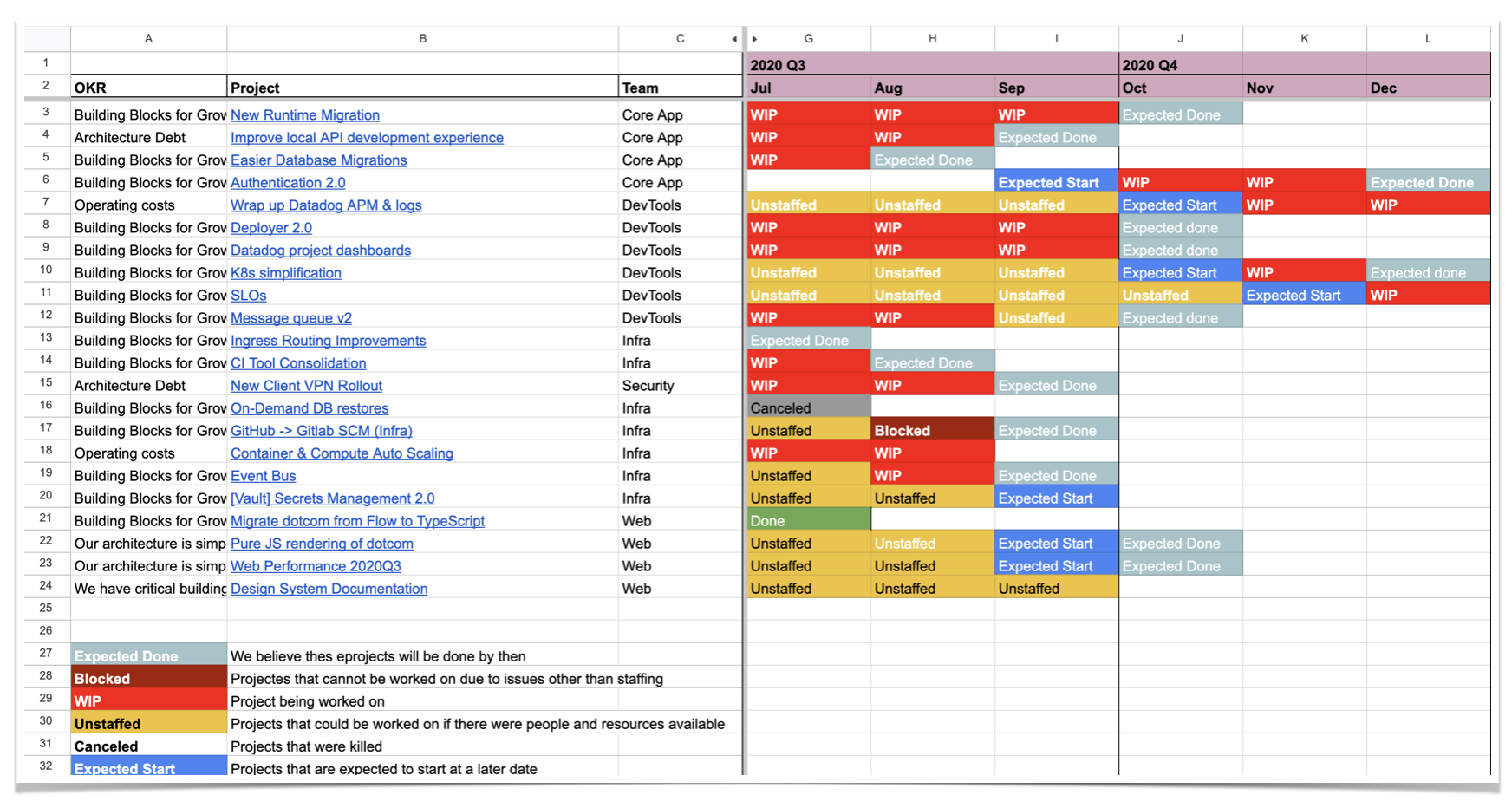

I usually keep a single spreadsheet listing all projects in our portfolio, each with an individual accountable for it. Each line has status and planning information, which goal (usually an OKR) it relates to, and the project name links to its charter. The project charter can be in any tool—e.g., some people have a Google Doc, others an Epic in Jira—as long as its contents follow the standard template.

Once every two weeks, we get together with all project owners for our project portfolio meeting, which is a topic that deserves its own article. I expect the project owner to keep the data on their projects in this spreadsheet always up-to-date, as this is the source of truth.

In return, I take on the administrative burden of using the information in this spreadsheet to populate whatever other systems and processes need this information—e.g., OKR tracking systems, company roadmaps, etc. They don’t have to worry about these; they only need to ensure that the project spreadsheet is current.

As you might imagine, this can be a lot of work. I’ve tried several strategies to avoid spending all my waking hours copying and pasting from this spreadsheet to other systems, everything from writing scripts that keep data in sync to, when I am really lucky, hiring a Chief of Staff to run this process.

Irrespective of your approach, you need to keep in mind that the best thing you can do to improve information quality is to reduce friction in the process.

Have recurring 1:1s not only with reports but also peers

I joke that every book on engineering management out there is basically 200 pages teaching you how to do 1:1 meetings_._ Joke or not, the reality is that holding regular 1:1 conversations with your reports is already a well-established practice in software engineering. Something less common, though, is having regular 1:1s with your peers and your manager’s peers.

Just like with reports, the structure and cadence of these meetings vary a lot from person to person and evolve over time. In my experience, executives prefer having some agenda instead of free-form conversation, while peers from departments that you don’t interact with much like to make it more of an informal chat.

Regardless of structure, regularly holding these conversations is crucial to building relationships. You really don’t want that you only interact with a peer when something is wrong. It is also a forum to discuss events that are not yet time-sensitive or early ideas that might or might not ever see the light of day. Finally, they also create an opportunity for serendipity, as someone might mention in passing something they didn’t think would impact your side of things but turns out is relevant to you and your teams.

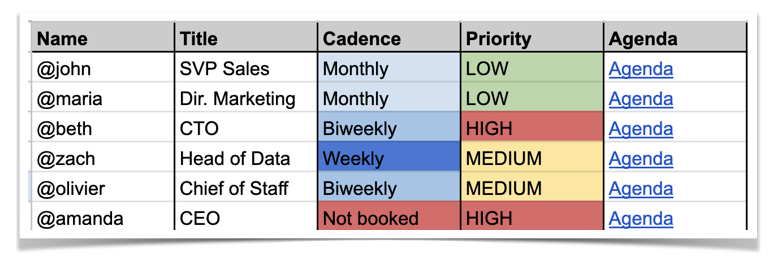

Calendaring software sucks, and unless you have an executive assistant, managing so many 1:1s at different cadences is a nightmare. You quickly lose track of who you should be meeting with and how often, forget to remove 1:1s that are not necessary anymore, etc.

I use a spreadsheet as a poor man’s CRM to tackle this. It’s pretty simple:

Besides the agenda shared with all participants, I keep a private document for every person I meet. Whenever something important but not urgent happens related to a person or their teams, I grab a screenshot or link to something that gives me context and paste it into this document, in reverse chronological order. This document is a great way to prevent losing track of things I need to bring to their attention but avoid dropping everything to act on it as they happen.

Avoid name-dropping

When someone is new to a role or a peer group, it is normal to feel awkward asking questions. One intuitive way to deal with the awkwardness is to shift blame, saying that you need this information or that thing done because “I need to report to <my manager> on it soon.” It is a super common defense mechanism, but it causes all sorts of issues.

The biggest issue is that it begs your direct reports or peers to question your role as a leader. Are you adding value, or are you there just to relay information up the totem pole? They are not wrong in asking this question, and if you don’t have a good answer, it might be a good time to consider where you are spending your time as a manager.

But even if they can see the value you add, student syndrome kicks in, and people will eventually send you the information just before you meet with the big boss. You won’t have enough time to digest the information and prepare for the meeting. More importantly, it jeopardizes your ability to do your actual job, which is to understand what is happening across your teams and make sure it’s aligned with the strategy for your division and company.

As tempting as it might be, never justify the need for information—or anything, really—by saying that your boss needs it. It is reasonable that people want to know why you need this information. Sharing context is a great way to have them help you strategize over the best way to achieve the desired outcome instead of just mindlessly giving you a status report. It is an excellent opportunity to improve their understanding of your role and the value you bring. And if you can’t clearly elaborate on that, it is a sign that you must first understand those yourself.

Plug: Where my attention is at

Leaders spend at least two hours every day just catching up with what’s going on first thing in the morning or when returning to their desks after hours of back-to-back meetings. We cannot talk about increasing efficiency in tech and ignore this waste.

My co-founder and I have debated the topic for years and recently decided it is an area worth exploring. We are leveraging the impressive power of the most recent developments in Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models to build something that was basically impossible just months ago.

Our platform plugs into the tools your team uses and learns not only from the artifacts your team produces but also from how people interact with them and collaborate amongst themselves. We use all this information to build an Interest Graph that we then use to bring relevant and timely updates to you based on topics and projects we know you care about.

And, because we know so much about the tools you use and how you use them, we can offer in-context automation that eliminates a large amount of manual labor that a leader needs to perform daily.

It’s like Github Copilot, but for managers.

Our first release focuses on helping new and seasoned managers at different levels sift through the noise and focus on what is important to them.

We are launching the first public version this Fall, and are currently onboarding partners for our private beta. If you want to see what we’re up to, you can add your name to the waitlist at Outropy.ai. If you want to know more about the company and our vision, you can reach me at phil <at> outropy.ai.