How I like to use OKRs

Recently I sent a memo to my teams at SeatGeek setting the scene around changes that I want to see in our OKR and planning processes. I’ve asked a few people from my professional network for feedback on this email, and it seems like this is something many other organizations struggle with. I am publishing a lightly-edited version of the memo below. Hopefully, it will be useful to some people facing similar challenges.

From: Phil Calçado

Date: Thu, Jan 9, 2020, 12:30 PM

Subject: OKRs in 2020

Hi team,

We are already a few weeks into 2020, but many teams are still working on their OKRs. This creates an opportunity for us to iterate on how we use this tool at SeatGeek. As a first step, I want to challenge the way we think about OKRs. For now, I don’t want to perform any drastic changes to the current process. What I want is to give all of you some context to help understand why I might nudge you one way or another now and in the future as we work on our goals and strategy.

There is a lot on OKRs in our wiki and all over the Internet. In this text, I want to focus on real-world usage and the challenges of this powerful tool. That is why I am skipping introductions and assuming that you have some familiarity with what are OKRs and probably have used them at SeatGeek or a previous employer.

One problem I have seen with our OKRs

After being through a few OKR cycles at SeatGeek, I am convinced that we tend to fall into a very common trap: we use OKRs the same way more traditional organizations use Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). To illustrate what I mean by this, I will use an oversimplified illustrative example.

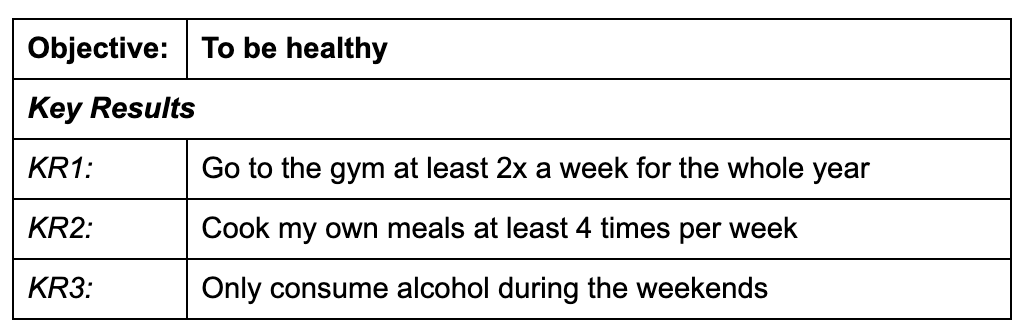

Let’s suppose that I am setting OKRs for my personal life. I decide that one of the most important Objectives I have is “To be healthy.” There are a few different ways to express this Objective in an OKR-based process. If we follow the typical SeatGeek style, we probably will build something like this:

Looking at the above, it might sound like a reasonable plan for someone to be healthy. The problem here is that even if we do all these things we set up to do, we can still be very unhealthy. For example, maybe you reduced your weekday alcohol consumption, but now you drink a lot more sugary drinks over the week, or perhaps you are cooking your own meals, but all you cook is mac and cheese.

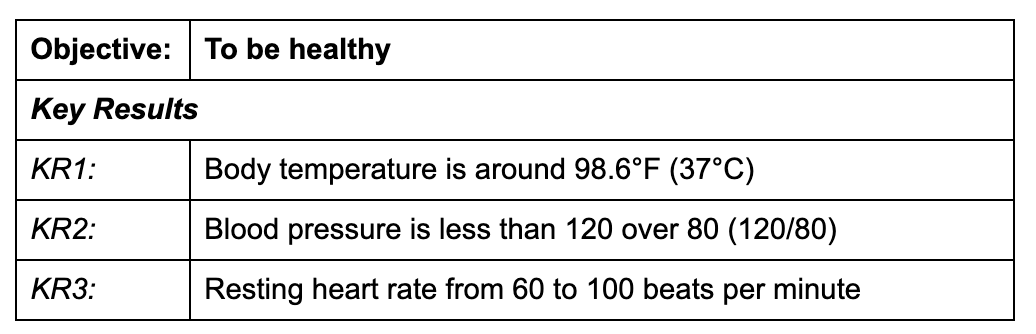

Instead, the way I have seen OKRs working well is when you use the Key Results as the test if you have achieved the Objective. Applying this mindset, let’s think about some of the things that are generally accepted as indicators that someone is “healthy”:

This is obviously an oversimplification to illustrate my point—I am not a doctor, and you should not follow anything I say about health—but I’m sure you got the idea.

To me, the most significant benefit of this format is that it focuses on the outcome instead of output. The number of projects, features, RFCs, or bugfixes we build and deploy are irrelevant. The only thing that matters is what material impact these had on the business and the experience of our users, partners, and employees.

It also helps us define what do I mean when we use terms such as “healthy.” Objectives will almost always be annoyingly hand-wavy, and the fact that they are open to interpretation tends to create some friction between teams. In this model, we are trying to define what we mean by “healthy” precisely. Different parties will argue a lot about what should be in it, but once the definition is agreed upon, it becomes a clear contract we all live by.

Another significant advantage of this style is that it gives teams a lot of freedom in how they will achieve that. What you have agreed on doing, i.e. your OKR, is just the what. Whoever is accountable for the OKR should be empowered to explore options for how they will get there. At the beginning of a quarter, teams will begin new projects and initiatives focusing on achieving their OKRs. They will use small and continuous releases to push their work to the users early and often. Still, they might observe that all this work doesn’t really have a material impact on the Key Results the way they thought it would. In a healthy OKR culture, teams in this situation should immediately regroup and pivot, exploring what other projects they should try to achieve these desired results.

OKRs, Roadmaps, and Project Portfolios

One interesting challenge in applying this model is that it often requires familiarity and access to essential metrics— often called KPIs, or Key Performance Indicators. It is perfectly fine, and even expected, for a Key Result to be that the team starts collecting data on some KPI we would like to use for future OKRs.

It is not impossible, though, that an Objective has one or a few Key Results as the delivery of some project or artifact, but this should be seen as a bad smell. It is an indication that we are probably missing some metric that can better reflect the desired outcomes.

Ideally, a team will look at their OKRs and start planning what efforts or projects they should start/keep/stop to achieve the desired results within the timeframe. This is generally called portfolio management, and it is something that I will be working closely with you all regularly.

If you want to learn more about this topic, there are a few good books on OKRs and similar goal-setting processes. My favorites are:

- Measure What Matters, the classic book by John Doerr

- High Output Management, Andy Grove’s seminal work on management and strategy

- The Advantage, which I see as Patrick Lencioni compiling most of his work on management in a single book

- OKRs, From Mission to Metrics: How Objectives and Key Results Can Help Your Company Achieve Great Things, an interesting collection of articles on real-world challenges in using OKRs by Francisco H. de MelloAs always, please reach out to me with any comments, feedback, or question.

Cheers