What Is a Service?

More and more people are developing systems based on services and all kinds of distributed business components. Content providers are exposing their content and metadata via APIs, and even big enterprises are making it easy for anyone to integrate with their systems. Internally, organisations of all sizes and from every industry have realised that the old way of using centralised databases as the main integration point between systems isn’t the way to go.

But when an organisation decides to expose a piece of software to be consumed by others, being those other engineers within the same organisation or third-party developers, a question arises: “So, what is a Service anyway? I’m asking for a friend…”

There are many books and articles about SOA and services, and each author seems to define those terms their own way. My main problem with the definitions I have learnt so far is that I just can’t see much difference between them and how we used to define a business component in the pre-SOA days of Component-Based Engineering (CBD).

For example, in their must-read book Software Component Factory, first published in 1999, Peter Herzum and Oliver Sims define a component as follows:

- A component is a self-contained software construct that has a defined use, has a run-time interface, can be autonomously deployed, and is built with foreknowledge of a specific component socket.

- A component socket is a software that provides a well-defined and well-known run-time interface to a supporting infrastructure into which the component will fit. A design-time interface alone is necessary but not sufficient because it does not exist in the run-time unless it’s implemented by some piece of software, that is, by the infrastructure.

- A component is built for composition and collaboration with other components.

- A component socket and the corresponding components are designed for use by a person with a defined set of skills and tools.

Our jargon has changed a lot since 1999, but even with a naïve substitution of component for service and socket for API, you will find that the definition above could easily be in a book on modern SOA published in 2009.

To make it more interesting, Herzum and Sims define a complete taxonomy of components, from very technical to business domains. They say the following about business components:

A business component is the software implementation of an autonomous business concept (entity or process). It consists of all the software artefacts necessary to represent, implement, and deploy a given business concept as an autonomous, reusable element of a larger distributed information system.

Technology has evolved a lot, so much that many topics covered in the book are obsolete. Nevertheless, the core concept is still the same. At this stage, I cannot see any fundamental difference between what we in 2009 call services and what these folks in 1999 were calling components.

But even without any fundamental difference, my experience as a practitioner of both CBD and SOA has shown me that there is a practical difference when it comes to the day-to-day use of distributed software. The way I’ve observed it, the main difference is that the SOA school is obsessed with reducing noise.

While implementations of Component-Based Development would focus on writing software that models the business needs, the limitations of technology and practices back then made it such that we would often have to change the business to adapt to the software. In SOA, our services model the existing business domain.

In other words, SOA is Domain-Driven Architecture while CBD would often result in Architecture-Driven Domain.

Let me try to clarify what I mean with an example.

The invisible component

Many years ago, I used to work as an engineer for a company that sold real-time billing software for telco companies. Once I was in a client to perform the installation of the new release of our main product, a very expensive piece of C code that ran only in some variants of expensive UNIX operating systems. Given that I happen to be in the client’s office, I was asked to take part in some discussions about a new project they were about to start.

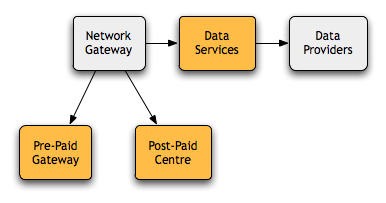

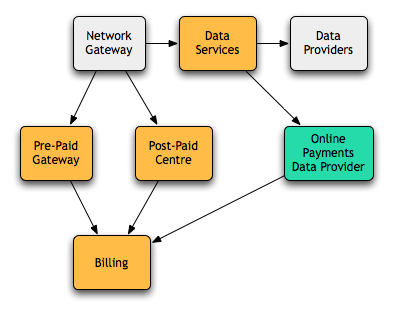

Up to that point, the architecture looked like this:

The three subsystems in orange were off-the-shelf pieces that the organisation had bought from my employer. Each of these subsystems was assembled from many components, each modelled as independent UNIX processes that communicate via shared memory or TCP.

The new project aimed at building a new product for the company Such product would allow their customers to pay their utility bills using mobile phones via USSD—this was in the early 200s, and back then it was considered bleeding edge. They told me that I should be in those meetings because some of the new systems might talk to my company’s system.

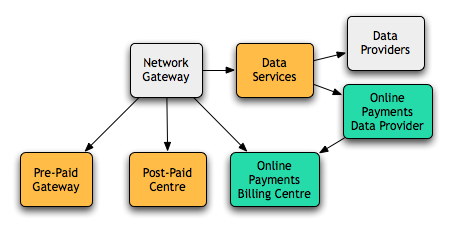

After a couple of meetings, I finally got a chance to grab a copy of the architecture diagram for the new system. It looked like this, with the new components in green:

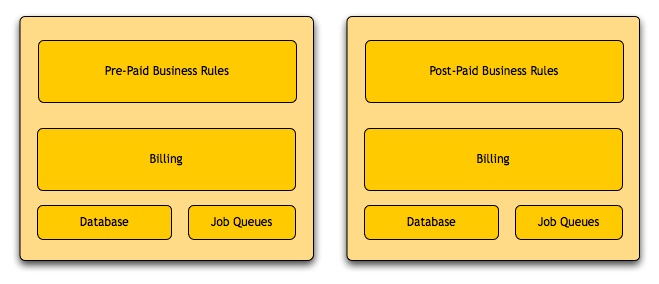

I was surprised that the organisation was trying to build yet another billing system. To understand my perspective, let’s look inside the Pre-paid Gateway and Post-Paid Centre subsystems and see each one of their individual components:

In the diagram above, the only real difference between each box is the Pre-Paid and Post-Paid components. Everything else was the same software, and it was generic enough that the organisation could add any other business rules to coordinate them. My employer was charging per subscriber, so there would be no extra cost for them to use the already-licensed software to power their new offering.

I tried to convince the group that they didn’t need to build a new system. After talking to some of the organisation’s engineers, the response I got was “I totally get what you are saying, but this decision was made by the business. To those folks, each one of these boxes is an island”.

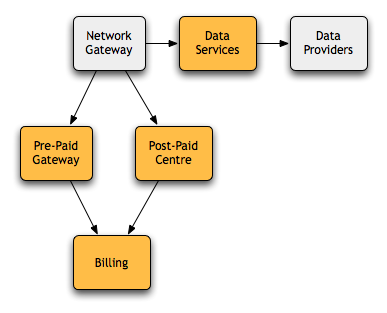

I spent a lot of time thinking about this whole thing. My conclusion was that our marketing strategy, focused on end-to-end billing verticals, led our customers to think of our systems in a different fashion from what we wanted. We invested a lot of engineering time in making sure our software had an open and extensible architecture, but all our customers saw were multiple black-boxes. Our per-subscriber pricing model meant that we had nothing to win from this, so maybe we should promote some of our internal to first-class components. We should do something like this:

This would better reflect our customer’s domain. I would then expect that when a new project comes up, they would be able to derive an architecture like this:

Some years after I left this employer, I found out that the marketing team had pushed engineering to move the architecture to the above mode. More interestingly, the marketing and business folk changed strategies completely and started treating the billing module as the most important product from their offering portfólio.

Everyone’s Architecture

The anecdote above illustrates how in modern software development we need to make sure that our services or components are visible not only to engineers but all stakeholders. In SOA, we want each discrete service to be part of the Ubiquitous Language. If you stick to the Ubiquitous Language, it gets easier to identify what is a Service and what is not.

A Service should be the implementation of a concept that the user understands. In the example above, this means exposing more of the internals of our system, but very often it worked the other way around.

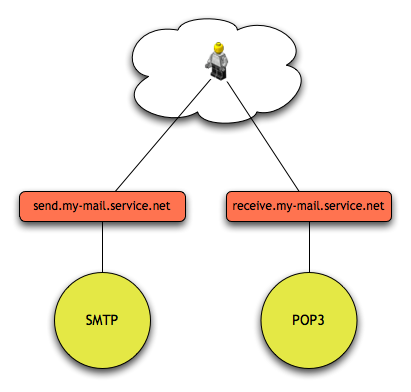

As an example, let’s suppose that you are going to offer access to an email provider over a HTTP webservice. For various reasons, when it comes to email one usually uses a protocol called POP3 to receive messages and a completely different one called SMTP to send them. Considering this, the easiest way to model your service might be to have two services, like pictured below:

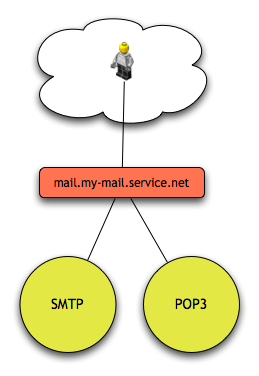

The main problem with this picture is that this is not how your customers and stakeholders think about email. They don’t understand the difference between these protocols, and they don’t care about our long history our Internet protocol idiosyncrasies. To achieve what feels more similar to what your users have in their minds it is probably better to simplify and offer a familiar metaphor:

We should have a single atomic service, even if internally two different protocols are used. This implementation detail isn’t relevant to the service, just like it wouldn’t be for the user interface.

The example was clearly an oversimplification, but this is a very common scenario. For example, we think of Google as a single web page with a text box and a “Search” button, and the API certainly tries its best to mimic a similar interface. The underlying system behind the most powerful search engine on the web is obviously not simple, but it doesn’t matter. If you are familiar with Google search products, it is very likely that you will find out how to use a given API in a few seconds. Because you understand the domain, all that’s left for you to learn is the syntax.

The important thing here is making sure that you model your services after how you want your stakeholders—engineers, customers, users—to think about your domain. We need to move the Ubiquitous Language we already use one step higher.