Pattern: Service Mesh

Since their first introduction many decades ago, we learnt that distributed systems enable use cases we couldn’t even think about before them, but they also introduce all sorts of new issues.

When these systems were rare and simple, engineers dealt with the added complexity by minimising the number of remote interactions. The safest way to handle distribution has been to avoid it as much as possible, even if that meant duplicated logic and data across various systems.

But our needs as an industry pushed us even further, from a few larger central computers to hundreds and thousands of small services. In this new world, we’ve had to start taking our head out of the sand and tackling the new challenges and open questions, first with ad-hoc solutions done in a case-by-case manner and subsequently with something more sophisticated. As we find out more about the problem domain and design better solutions, we start crystallising some of the most common needs into patterns, libraries, and eventually platforms.

What happened when we first started networking computers

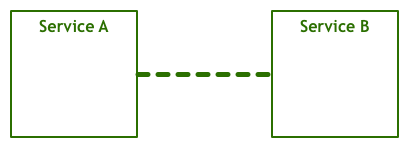

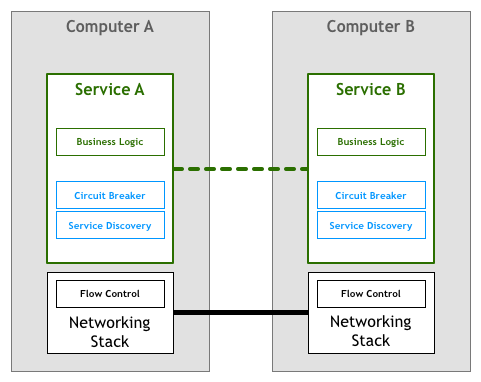

Since people first thought about getting two or more computers to talk to each other, they envisioned something like this:

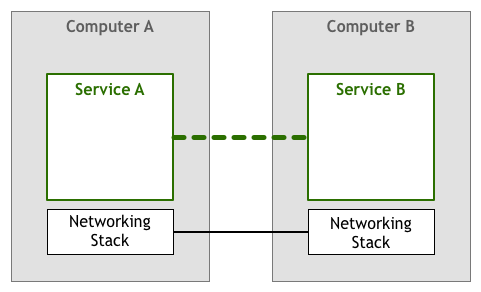

A service talks to another to accomplish some goal for an end-user. This is an obviously oversimplified view, as the many layers that translate between the bytes your code manipulates and the electric signals that are sent and received over a wire are missing. The abstraction is sufficient for our discussion, though. Let’s just add a bit more detail by showing the networking stack as a distinct component:

Variations of the model above have been in use since the 1950s. In the beginning, computers were rare and expensive, so each link between two nodes was carefully crafted and maintained. As computers became less expensive and more popular, the number of connections and the amount of data going through them increased drastically. With people relying more and more on networked systems, engineers needed to make sure that the software they built was up to the quality of service required by their users.

And there were many questions that needed to be answered to get to the desired quality levels. People needed to find ways for machines to find each other, to handle multiple simultaneous connections over the same wire, to allow for to machines to talk to each other when not connected directly, to route packets across networks, encrypt traffic, etc.

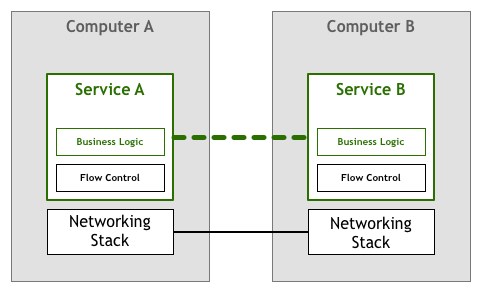

Amongst those, there is something called flow control, which we will use as our example. Flow control is a mechanism that prevents one server from sending more packets than the downstream server can process. It is necessary because in a networked system you have at least two distinct, independent computers that don’t know much about each other. Computer A sends bytes at a given rate to Computer B, but there is no guarantee that B will process the received bytes at a consistent and fast-enough speed. For example, B might be busy running other tasks in parallel, or the packets may arrive out-of-order, and B is blocked waiting for packets that should have arrived first. This means that not only A wouldn’t have the expected performance from B, but it could also be making things worse, as it might overload B that now has to queue up all these incoming packets for processing.

For a while, it was expected that the people building networked services and applications would deal with the challenges presented above in the code they wrote. In our flow control example, it meant that the application itself had to contain logic to make sure we did not overload a service with packets. This networking-heavy logic sat side by side with your business logic. In our abstract diagram, it would be something like this:

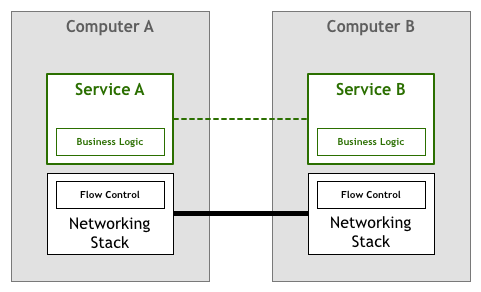

Fortunately, technology quickly evolved and soon enough standards like TCP/IP incorporated solutions to flow control and many other problems into the network stack itself. This means that that piece of code still exists, but it has been extracted from your application to the underlying networking layer provided by your operating system:

This model has been wildly successful. There are very few organisations that can’t just use the TCP/IP stack that comes with a commodity operating system to drive their business, even when high-performance and reliability are required.

What happened when we first started with microservices

Over the years, computers became even cheaper and more omnipresent, and networking stack described above has proven itself as the de-facto toolset to reliably connect systems. With more nodes and stable connections, the industry has played with various flavours of networked systems, from fine-grained distributed agents and objects to Service-Oriented Architectures composed of larger but still heavily distributed components.

This extreme distribution brought up a lot of interesting higher-level use cases and benefits, but it also surfaced several challenges. Some of these challenges are completely new, but others are just higher-level versions of the ones we discussed when talking about raw networks.

In the 90s, Peter Deutsch and his fellow engineers at Sun Microsystems compiled “The 8 Fallacies of Distributed Computing”, in which he lists some assumptions people tend to make when working with distributed systems. Peter’s point is that these, might have been true in more primitive networking architectures or the theoretical models, but they don’t hold true in the modern world:

- The network is reliable

- Latency is zero

- Bandwidth is infinite

- The network is secure

- Topology doesn’t change

- There is one administrator

- Transport cost is zero

- The network is homogeneous

Denouncing the list above as “fallacies” means that engineers cannot just ignore these issues, they have to explicitly deal with them.

To complicate matters further, moving to even more distributed systems—in what we often call a microservices architecture—has introduced new needs on the operability side. We discussed some of these in detail before, but here is a quick list of what one has to deal with:

- Rapid provisioning of compute resources

- Basic monitoring

- Rapid deployment

- Easy to provision storage

- Easy access to the edge

- Authentication/Authorisation

- Standardised RPC

So while the TCP/IP stack and general networking model developed many decades ago is still a powerful tool in making computers talk to each other, the more sophisticated architectures introduced another layer of requirements that, once more, have to be fulfilled by engineers working in such architectures.

As an example, consider service discovery and circuit breakers, two techniques used to tackle several of the resiliency and distribution challenges listed above.

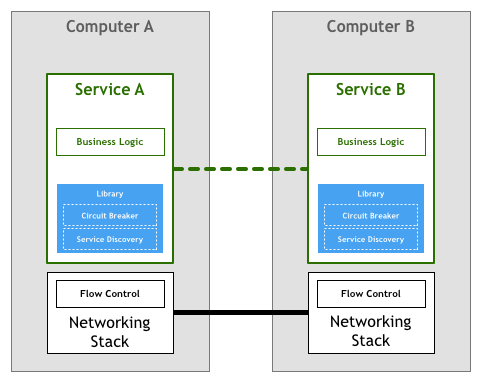

As history tends to repeat itself, the first organisations building systems based on microservices followed a strategy very similar to those of the first few generations networked computers. This means that the responsibility of dealing with the requirements listed above was left to the engineer writing the services.

Service discovery is the process of automatically finding what instances of service fulfil a given query, e.g. a service called Teams needs to find instances of a service called Players with the attribute environment set to production. You will invoke some service discovery process which will return a list of suitable servers. For more monolithic architectures, this is a simple task usually implemented using DNS, load balancers, and some convention over port numbers (e.g. all services bind their HTTP servers to port 8080). In more distributed environments, the task starts to get more complex, and services that previously could blindly trust on their DNS lookups to find dependencies now have to deal with things like client-side load-balancing, multiple different environments (e.g. staging vs. production), geographically distributed servers, etc. If before all you needed was a single line of code to resolve hostnames, now your services need many lines of boilerplate to deal with various corner cases introduced by higher distribution.

Circuit breakers are a pattern catalogued by Michael Nygard in his book Release It. I like Martin Fowler’s summary for the pattern:

The basic idea behind the circuit breaker is very simple. You wrap a protected function call in a circuit breaker object, which monitors for failures. Once the failures reach a certain threshold, the circuit breaker trips, and all further calls to the circuit breaker return with an error, without the protected call being made at all. Usually you’ll also want some kind of monitor alert if the circuit breaker trips.

These are great simple devices to add more reliability to interactions between your services. Nevertheless, just like everything else they tend to get much more complicated as the level of distribution increases. The likelihood of something going wrong in a system raises exponentially with distribution, so even simple things like “some kind of monitor alert if the circuit breaker trips” aren’t necessarily straightforward anymore. One failure in one component can create a cascade of effects across many clients, and clients of clients, triggering thousands of circuits to trip at the same time. Once more what used to be just a few lines of code now requires loads of boilerplate to handle situations that only exist in this new world.

In fact, the two examples listed above can be so hard to implement correctly that large, sophisticated libraries like Twitter’s Finagle and Facebook’s Proxygen became very popular as means to avoid rewriting the same logic in every service.

The model depicted above was followed by the majority of the organisations that pioneered the microservices architecture, like Netflix, Twitter, and SoundCloud. As the number of services in their systems grew, they also stumbled upon various drawbacks of this approach.

Probably the most expensive challenge, even when using a library like Finagle, is that an organisation will still need to invest time from its engineering team in building the glue that links the libraries with the rest of their ecosystem. Based on my experiences at SoundCloud and DigitalOcean I would estimate that following this strategy in a 100-250 engineers organisation, one would need to dedicate 1/10 of the staff to building tooling. Sometimes this cost is explicit as engineers are assigned to teams dedicated to building tooling, but more often the price tag is invisible as it manifests itself as time taken away from working on your products.

A second issue is that the setup above limits the tools, runtimes, and languages you can use for your microservices. Libraries for microservices are often written for a specific platform, be it a programming language or a runtime like the JVM. If an organisation uses platforms other than the one supported by the library, it often needs to port the code to the new platform itself. This steals scarce engineering time. Instead of working on their core business and products, engineers have to, once again, build tools and infrastructure. That is why some medium-sized organisations like SoundCloud and DigitalOcean decided to support only one platform for their internal services—Scala and Go respectively.

One last problem with this model worth discussing is governance. The library model might abstract the implementation of the features required to tackle the needs of the microservices architecture, but it is still in itself a component that needs to be maintained. Making sure that thousands of instances of services are using the same or at least compatible versions of your library isn’t trivial, and every update means integrating, testing, and re-deploying all services—even if the service itself didn’t suffer any change.

The next logical step

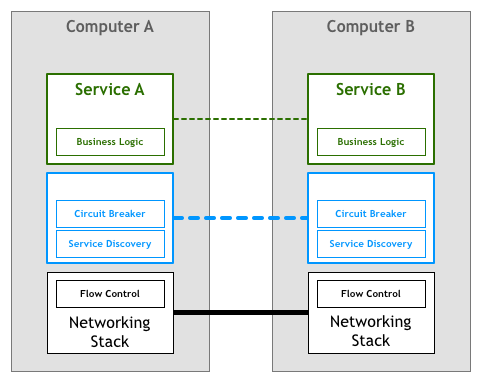

Similarly to what we saw in the networking stack, it would be highly desirable to extract the features required by massively distributed services into an underlying platform.

People write very sophisticated applications and services using higher level protocols like HTTP without even thinking about how TCP controls the packets on their network. This situation is what we need for microservices, where engineers working on services can focus on their business logic and avoid wasting time in writing their own services infrastructure code or managing libraries and frameworks across the whole fleet.

Incorporating this idea to our diagram, we could end up with something like the following:

Unfortunately, changing the networking stack to add this layer isn’t a feasible task. The solution found by many practitioners was to implement it as a set of proxies. The idea here is that a service won’t connect directly to its downstream dependencies, but instead all of the traffic will go through a small piece of software that transparently adds the desired features.

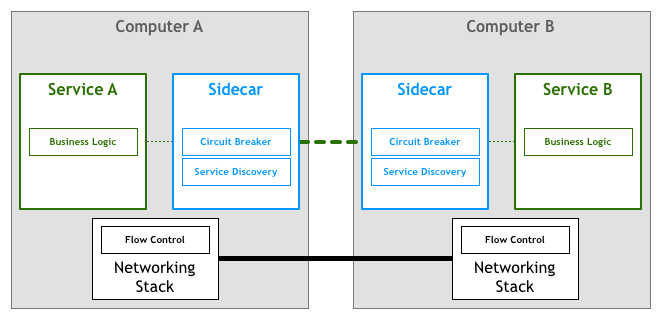

The first documented developments in this space used the concept of sidecars. A sidecar is an auxiliary process that runs aside your application and provides it with extra features. In 2013, Airbnb wrote about Synapse and Nerve, their open-source implementation of a sidecar. One year later, Netflix introduced Prana, a sidecar dedicated to allowing for non-JVM applications to benefit from their NetflixOSS ecosystem. At SoundCloud, we built sidecars that enabled our Ruby legacy to use the infrastructure we had built for JVM microservices.

While there are several of these open-source proxy implementations, they tend to be designed to work with specific infrastructure components. As an example, when it comes to service discovery Airbnb’s Nerve & Synapse assume that services are registered in Zookeeper, while for Prana one should use Netflix’s own Eureka service registry for that.

With the increasing popularity of microservices architecture, we have recently seen a new wave of proxies that are flexible enough to adapt to different infrastructure components and preferences. The first widely known system on this space was Linkerd, created by Buoyant based on their engineers’ prior work on Twitter’s microservices platform. Soon enough, the engineering team at Lyft announced Envoy which follows a similar principle.

The Service Mesh

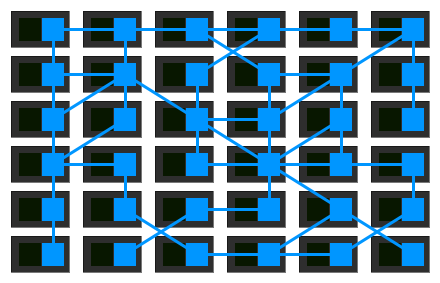

In such model, each of your services will have a companion proxy sidecar. Given that services communicate with each other only through the sidecar proxy, we end up with a deployment similar to the diagram below:

Buoyant’s CEO William Morgan made the observation that the the interconnection between proxies form a mesh network. In early 2017, William wrote a definition for this platform, and called it a Service Mesh:

A service mesh is a dedicated infrastructure layer for handling service-to-service communication. It’s responsible for the reliable delivery of requests through the complex topology of services that comprise a modern, cloud native application. In practice, the service mesh is typically implemented as an array of lightweight network proxies that are deployed alongside application code, without the application needing to be aware.

Probably the most powerful aspect of his definition is that it moves away from thinking of proxies as isolated components and acknowledges the network they form as something valuable in itself.

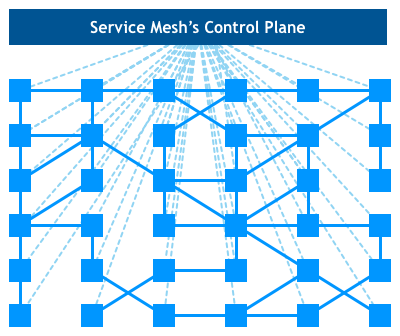

As organisations move their microservices deployments to more sophisticated runtimes like Kubernetes and Mesos, people and organisations have started using the tools made available by those platforms to implement this idea of a mesh network properly. They are moving away from a set of independent proxies working in isolation to a proper, somewhat centralised, control plane.

Looking at our bird’s eye view diagram, we see that the actual service traffic still flows from proxy to proxy directly, but the control plane knows about each proxy instance. The control plane enables the proxies to implement things like access control and metrics collection, which requires cooperation:

The recently announced Istio project is the most prominent example of such system.

It is still too early to fully understand the impacts of a Service Mesh in larger scale systems. Two benefits of this approach are already evident to me. First, not having to write custom software to deal with what are ultimately commodity code for microservices architecture will allow for many smaller organisations to enjoy features previously only available to large enterprises, creating all sorts of interesting use cases. The second one is that this architecture might allow us to finally realise the dream of using the best tool/language for the job without worrying about the availability of libraries and patterns for every single platform.

Acknowledgements

Monica Farrell, Rodrigo Kumpera, Etel Sverdlov, Dave Worth, Mauricio Linhares, Daniel Bryant, Fabio Kung, and Carlos Villela gave feedback on drafts of this article.

Revision History

- 03/08/2017 - First published

- 05/08/2017 - Incorporated feedback